Some Ratio Thingy—A Cautionary Tale

by Aren Lew

The story you are about to read is true(ish). The names have been changed to protect those whose formal math education misled them to believe that memorized procedures are more valuable than their own reasoning.

Picture the scene … a middle school math classroom somewhere in America circa 1987:

Richard sits at his desk. At the board, the teacher demonstrates how to set up a proportion by setting two ratios equal to each other. “Now,” the teacher states, “the rest is simple. Just cross-multiply and divide to find the missing number.” Richard takes notes.

The teacher then hands out a worksheet with 20 decontextualized proportions and two word problems at the bottom. Richard and his peers work on it for the rest of the class period and take home the unfinished part for homework.

Richard finishes the worksheet at home. He’s not sure he identified the ratios in the two word problems and set up the proportions correctly, but he got an answer for each of them. It’s good enough to turn in. He’ll get credit for trying. It doesn’t seem to matter that much because today the class has moved on to multiplying decimals.

Present day:

Richard has made it through—managed to pass middle school math classes, even high school ones. He has a college degree and a good career. He doesn’t do a lot of math in his day-to-day life—or at least he doesn’t often see anything that looks like the math he sat through in school

But today is different. Today Richard finds himself in the middle of a real-world word problem. Here’s the whole grisly scene:

Richard has a large bag of potato chips. Being health conscious, he decides to divide it up into single serving portions. According to the bag, the whole bag contains five servings that have 120 calories each… but … Richard divides the chips into only four portions! What to do now? How many calories are in one of those servings?

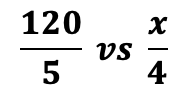

Richard does not despair. He remembers those carefree middle school days. There was something he learned in school that should help here. He sets up a proportion:

“That looks pretty mathy,” he thinks. “It should work.”

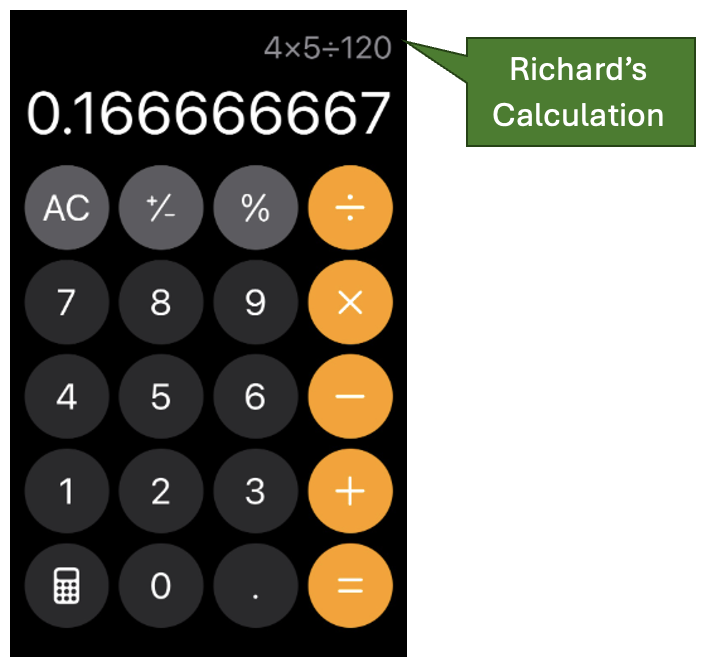

He gets out his calculator to solve:

Richard scratches his head. That doesn’t seem right. He thinks…

I didn’t make five portions like it said on the bag—it said that if I did, they would be 120 calories each.

I used the whole bag to make only four portions… which means I put more chips in each bag… so each bag should have more than 120 calories.

Richard looks again at his calculator. It must be, he decides, that the calories per bag is 166.666667 or about 166 calories. This makes sense.

Proud of his work, Richard texts his cousin, a math teacher, and shares his reasoning, saying, “I did some ratio thingy and some math and got about 166 calories per bag.”

Upon being further pressed to explain his reasoning, Richard considers… “Wait, maybe I could just split the extra calories from the fifth portion among the other four. That would mean adding 30 calories to each bag, so it would be 150 calories per bag.”

Which answer should Richard trust? The one based on a ratio thingy he learned in school or the one grounded in context and his own ability to make sense?

How might Richard’s faith in his own reasoning and perception of himself as a mathematical thinker be different if, instead of being shown what to do in school, he had been given opportunities to engage in productive struggle and value his own thinking? It’s something to think about as we choose materials and activities for our classes. If our long-term goal is for students to be confident and capable mathematical thinkers in the real world, we need to nurture them as thinkers, not just show them what to do to solve problems that show up on worksheets and tests.

Aren Lew has worked in the field of adult numeracy for over ten years, both as a classroom teacher and providing professional development for math and numeracy teachers. They are a consultant for the SABES Mathematics and Adult Numeracy Curriculum & Instruction PD Team at TERC where they develop and facilitate trainings and workshops and coach numeracy teachers. They are the treasurer for the Adult Numeracy Network.